Engineering Decisions

Design Decisions

Consistency of the user experience

Most A/B testing platforms incorporate some form of context into the logic that assigns a particular user or request to a particular feature or experience. This ensures that a particular user continues to experience the same variant across multiple requests. But what context you want to provide may depend on the type of application and the type of feature that you are testing.

For example, when you are testing a feature that is not dependent on user identity or behavior, such as the color of a button or the placement of a banner on a website, it may be appropriate to randomly assign users to the control or treatment group on each page load or request. This helps to ensure that the results are not affected by any systematic differences between users.

On the other hand, when you are testing a feature that is dependent on user behavior during a single session, such as the effectiveness of a product recommendation algorithm, it may be important to ensure that the user receives the same variant throughout their session. This helps to ensure that the user's behavior is consistent across the control and treatment groups, and that any differences in behavior can be attributed to the feature being tested.

Finally, when you are testing a feature that is dependent on user identity or behavior over time, such as the effectiveness of a personalized email marketing campaign, it may be appropriate to tie the variant to a particular email address or user ID. This helps to ensure that the user receives the same variant each time they interact with the product or service, and that any differences in behavior can be attributed to the feature being tested rather than user variability.

Throughout the Test Lab design process, the goal was flexibility. In the interest of flexibility, we introduce the user_id as part of the SDK client’s context to allow the developer to specify what they want to use to assign a particular experience to a user. As part of the client instantiation process, a default context is assigned, which includes a unique UUID assigned to the user_id property and the IP address of the incoming request assigned to the ip property of the context.

If the developer wants this randomly generated UUID to be used to evaluate the feature(s) for the request, then the default context can be used. Otherwise, the developer has the opportunity to update the context using the update_context method, passing a new value to the user_id and/or ip properties. As long as it is a unique string, the user_id can represent a random value, a session identifier, or any other identifier that meets the needs of the experiment.

The value that is assigned to the user_id is then used to evaluate the feature. Since the assignment logic is deterministic, every time a feature is evaluated with a particular user_id, it will return the same value. So the value chosen for the user_id will determine the feature assignment in the application.

Limiting users to one concurrent experiment

At its core, Test Lab is an experimentation platform, and we wanted to ensure that data would not be compromised by running concurrent experiments on a single user. For example, if a user were exposed to one variant of Experiment A and another variant of Experiment B, then how would be be able to determine if a user’s behavior was due to exposure to Experiment A, Experiment B, or some combination of the two?

One approach: multivariate analysis

One answer to this question is multivariate analysis. To perform multivariate analysis in an A/B testing platform, you would first need to identify the different variables being tested and the possible combinations of these variables. For example, if a website is being tested with two different layouts and three different headlines, there are six possible combinations to test.

Once the experiments have been conducted and the data has been collected, statistical methods such as regression analysis or analysis of variance (ANOVA) can determine the effects of each variable on the outcome of the experiment. These methods allow for the isolation of the impact of each variable and determine which combinations of variables are most effective.

While multivariate analysis can be a powerful tool for determining the individual effects of different variables in A/B testing, there are also some downsides to consider:

- Increased complexity: Multivariate analysis will most likely be more complex than simpler A/B testing methods, as it involves analyzing the effects of multiple variables simultaneously. This can make it more difficult to interpret the results and identify the most effective combinations of variables.

- Increased sample size requirements: Because multivariate analysis involves testing multiple variables simultaneously, it typically requires a larger sample size than simpler A/B testing methods. This can increase the time and resources required to conduct experiments and may make it more difficult to obtain statistically significant results.

- Increased risk of false positives: Multivariate analysis can increase the risk of false positives, as the more variables that are tested, the greater the likelihood of finding statistically significant results by chance. This can make it more difficult to determine which variables are truly having an impact on the outcome of the experiment.

- Increased risk of overfitting: Multivariate analysis can also increase the risk of overfitting, as the more variables that are tested, the greater the risk of finding a combination of variables that performs well on the test data but does not generalize well to new data. This can lead to inaccurate or misleading results.

In short, while multivariate analysis is a perfectly reasonable approach for applications with very large user bases that provide sufficient power to tease out multivariate effects, it is less likely to be a good fit for a platform like Test Lab that is tailored to meet the needs of applications with a more modest-sized user base.

Test Lab approach: user-blocks

Instead, we decided on an approach that would ensure that a user was exposed to only one experiment at a time. This starts with the Admin UI, where our user interface ensures that a maximum of 100% of users can be participating in experiments at any given point in time.

Next, when the SDK polls the Test Lab backend server for feature configuration, the backend server provides a list of user-blocks indicating which “blocks” of users are allocated to each experiment. This list is updated over time to account for experiments that have completed (freeing up blocks of allocated users) and new experiments that are starting up and being assigned to new blocks of allocated users. The key is that once a block of users has been allocated to an experiment, it remains allocated to that experiment until the experiment has completed.

Granularity of user-blocks

As described in the last section, Test Lab allows users to be assigned to no more than one experiment at a time. In other words, no more than 100% of the user-base can be allocated to experiments at any point in time.

When creating or updating experiments, the Admin UI evaluates the minimum percentage of the user-base that is available throughout the duration of the experiment, and that is the maximum percentage that can be enrolled in a new or updated experiment. This ensures that the user-base is limited to no more than one experiment per user.

One decision we made was to allocate users to experiments in 5% blocks.

The assignment logic would be the same if we used blocks of 1%, so why use 5%?

The use case for Test Lab is smaller applications that are just getting started with A/B testing, and our current assumption is that these applications would have a relatively small user base. It is possible that experiments could take a long time to reach statistical significance, even with enrolling 5% of users in a particular experiment. If we allowed for the creation of experiments with as few as 1% of users enrolled, it could be very difficult to obtain meaningful data unless the effect size were very large.

Therefore, as a starting point, we decided that 5% was a reasonable minimum of the user-base to enroll in an experiment. This still allows for up to 20 concurrent experiments, which seems more than sufficient for a typical Test Lab user. If users were expecting higher-than-expected traffic that could support even more concurrent experiments, then the logic could be updated to allow for more granular user-blocks.

Polling to retrieve updated feature data

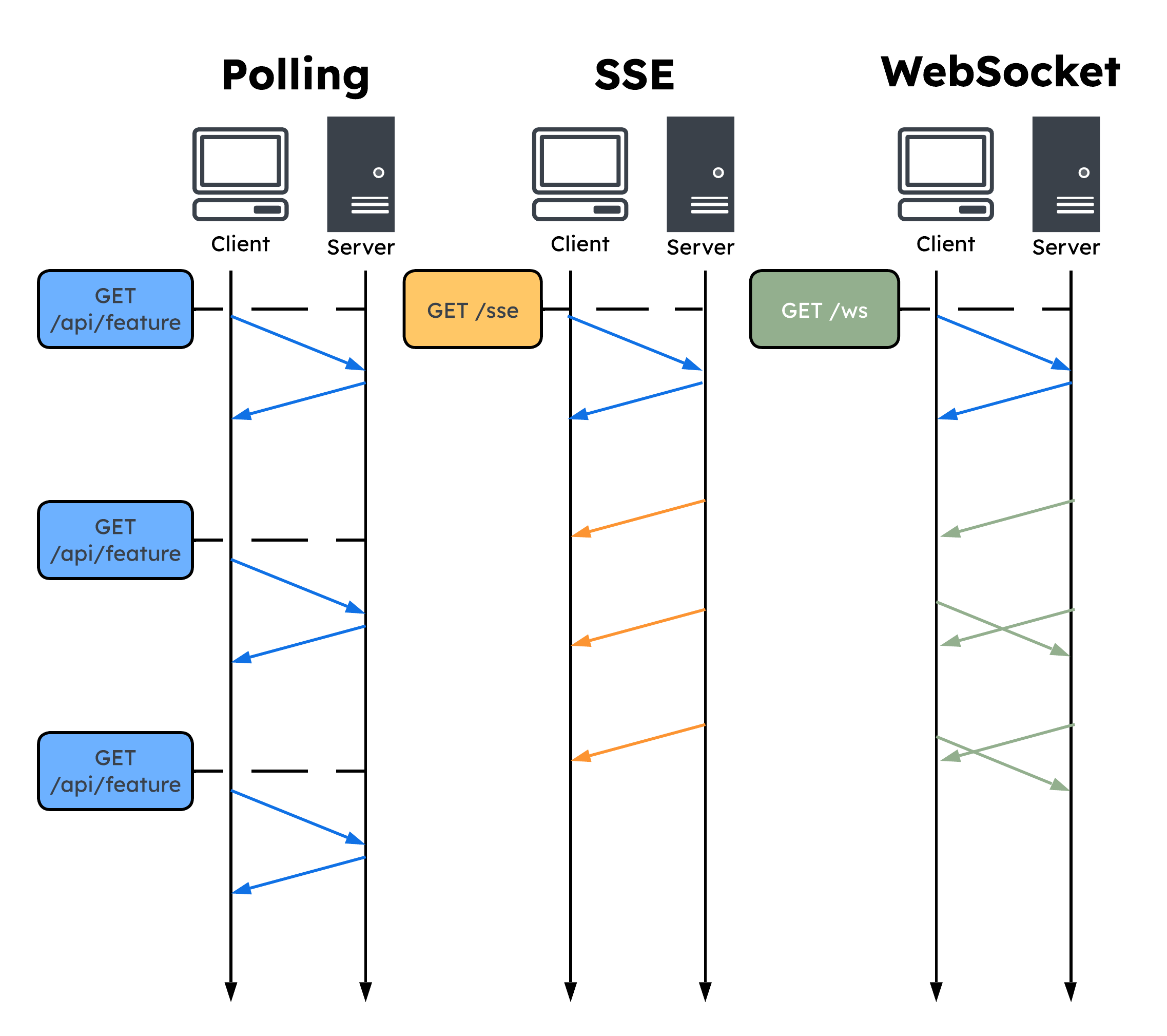

The Test Lab team considered a number of options for ensuring that the in-memory representation of the feature configuration created by the SDK remains up to date as features change over time, including:

Polling: a client-server communication technique where the client sends requests to the server at intervals to receive updates

Server-sent events (SSEs): a unidirectional, server-initiated communication technique where the server sends updates to the client as soon as new data is available

Websockets: a bidirectional, real-time communication protocol that allows full-duplex communication between the client and server

Ultimately, the Test Lab team opted to use polling for several key reasons:

- Simplicity: Polling is a simple approach to fetching data from a server. It involves making periodic requests to the server at a predefined interval to check for updates. This makes it a good option for smaller applications that don't require real-time updates and don't need the additional complexity of websockets or SSE.

- Compatibility: Polling is widely supported by all modern browsers and doesn't require any additional server-side infrastructure or configuration, making it a good choice when compatibility is a concern.

- Resource efficiency: Polling can be more resource-efficient than websockets or SSE in situations where the amount of data being transmitted is relatively small or infrequent. This is because websockets and SSE maintain a persistent connection, which can consume more resources on both the client and server. The Test Lab server only responds with new data when the feature configuration has changed, which makes polling an efficient choice.

- Control: With polling, the client has more control over the frequency of requests and can adjust the polling interval to suit its needs. This can be useful in situations where the rate of updates is variable or unpredictable. In the interest of flexibility, Test Lab offers control of the polling interval to the client application.